Humanoid Robotics: Are we losing our humanity?

- Expertise

- Temps de lecture : 13 min

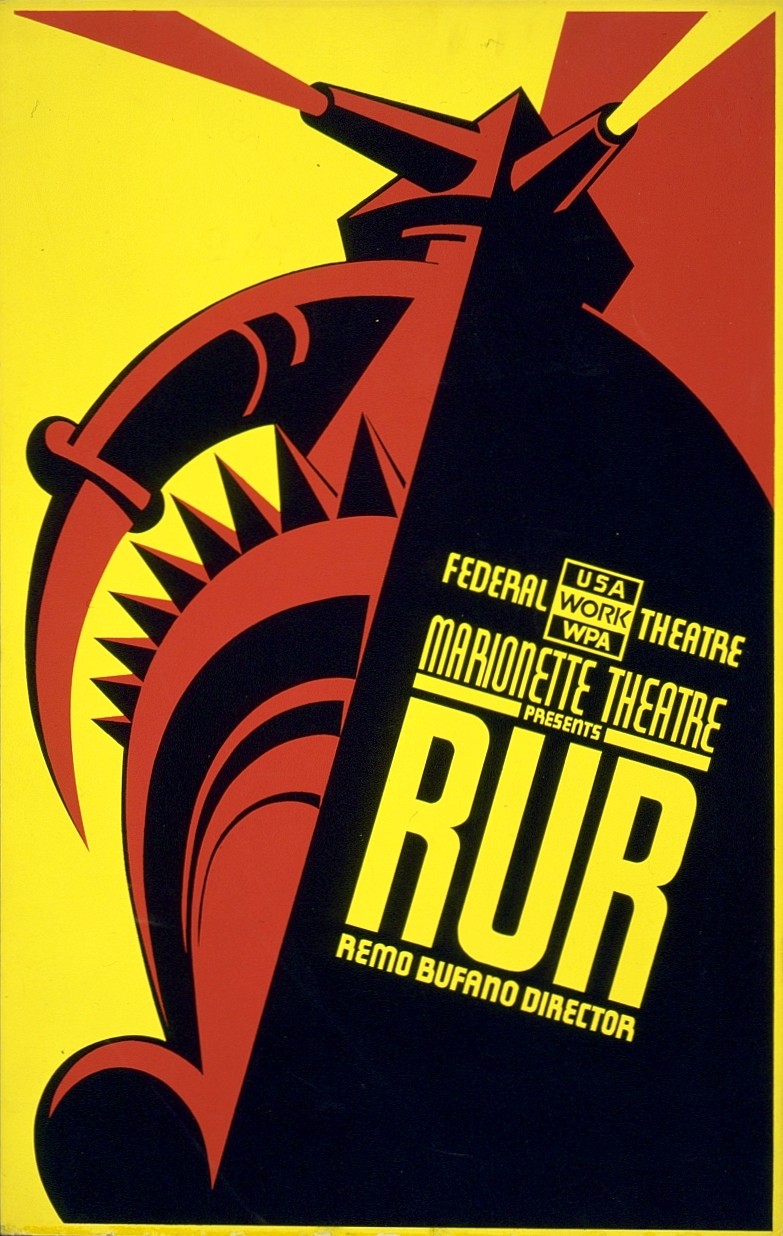

Since the beginning of robotics, at least from the moment when the term “Robot” was used in this context by the Čapek brothers in 1921, robots have been represented in a human form: the humanoid. The image of a robot navigated between fantasies and industrial needs under the guise of productivity.

100 years after the creation of the word “robot”, we invite you, through this interview with Sacha Stojanovic, Founding President of Meanwhile and a graduate of Sciences Po Paris in Digital Humanities, to ask yourself the right questions. What world do we want to leave to future generations?

I. What is a robot today?

Before defining what a robot is today, it is important to come back to the semantics of the word “Robot”. The term “Robot”, more precisely “Robota”, was first used in 1921 to designate what today looks like a robot, in a play by the name of R.U.R., created by the Čapek brothers . “Robota” comes from Czech and means “chore”. In this play, the Čapek brothers describe a world in which, at least at the beginning of the story, human beings and humanoid robots coexist. The first time that the term “Robot” is used, it is therefore to define, if we are interested in the object itself, essentially a humanoid robot, while obscuring the associated service.

It was only fifty years later that industrial robots called robotic arms appeared. The name “robotic arm” is justified by its shape and dynamics. It was in 1971 that the inventor A. Burch filed the first patent evoking the industrial robot.

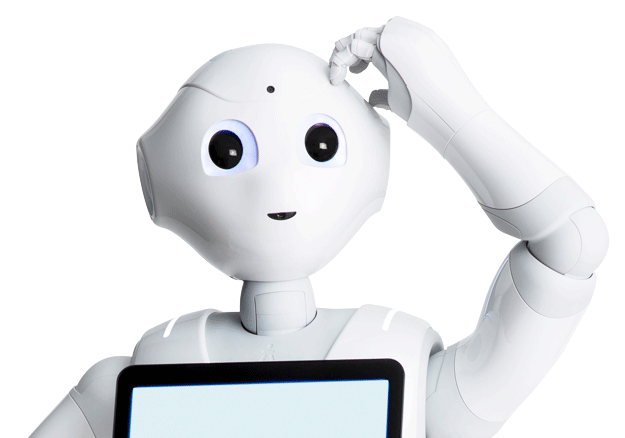

Sacha Stojanovic points out that the word “robot” has become a portmanteau word. Indeed, the term robotics today designates many things: kitchen robot, robot vacuum cleaner, articulated arm for industry, robot dog, and the supreme being – the one who is at the very top of the obsolete pyramid of the robotic species – the humanoid robot, which we have even succeeded in sexing: the gynoids and the androids.

But if we define the word “robot” today, we would say that a robot is a complex machine, capable of carrying out a certain number of tasks autonomously or semi-autonomously. Some robots are more complex than others, they are said to be indeterministic and use artificial intelligence bricks.

II. Are we right to use the term robot to refer to mobile robots?

If we are interested in the semantics of the word robot, it was used to designate humanoid robots and subsequently industrial robotic arms. “Indeed, there is a big difference between industrial robots and mobile robotics, so much so that we can wonder if it’s the same job” challenges Sacha.

Industrial robotic arms are programmed to perform a certain number of tasks, taking into account signals sent by more or less complex sensors (presence sensors, 3D cameras, etc.), unlike intelligent mobile robots, equipped with different layers. software, including one inspired by a technique called SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping). The mobile robot is indeterministic in its trajectory and is content to respect safety rules. On its own, in the event that a corridor is obstructed, the robot will decide to take another corridor. Also, in the event that an obstacle presents itself to it, it will recalculate its trajectory to avoid it and circumvent it. Thanks to the SLAM algorithm, it is possible to operate several mobile robots together; this requires an application layer called “Fleet Manager”. This will manage the crossing of robots in order to avoid singularities, or the scheduling of tasks. We can therefore conclude that autonomous mobile robots are very complex and meet the criteria of the contemporary definition of the word “robot”.

III. What is humanoid robotics?

The term humanoid means “human-like”. Generally, humanoid robots have a torso with a head, two arms and two legs, although some models represent only a part of the body, for example from the waist. Some humanoid robots may have a “face”, with “eyes” and a “mouth”. “An android is a human-shaped robot, etymologically that “which looks like a man”” and “A gynoid is a robot with the appearance of a woman.”

The humanoid robot, in the contemporary sense of the term, was first born in the minds of writers like Karel Čapek, whom we mentioned above, in 1921, or like Isaac Asimov with the three laws of robotics:

- a robot may not harm a human being, nor, by remaining passive, allow a human being to be exposed to danger;

- a robot must obey orders given to it by a human unless such orders conflict with the first law;

- a robot must protect its existence as long as that protection does not conflict with the first or second law.

To date, regarding the mechanical aspect, there are different types of humanoid robots:

1- The bipedal robot capable of moving in a more or less complex known space or even in an unknown space then rather simple.

2- The clone robot imitating the human with more or less success

3- The social robot, less humanoid because of its appearance, endowed with a Kawaii form, good at exchanging with a person and trying as much as possible to help him.

There are 2 complementary challenges in humanoid robotics: artificial intelligence (AI) on one side and mechatronics on the other. Regarding AI, many are still wondering whether it will be local – that is, embedded in the humanoid robot – or remote. In the first case, the issues are the necessary energy and the management of the self-learning system. In the second case, it will be necessary to focus on communication and particularly on security issues.

Concerning mechatronics, the problem of the “Zero Moment Point” (ZMP) is still a challenge to be met: knowing how to stand, walk, run… while remaining in balance, is an extremely complex exercise for a bipedal robot. It took a few years to get a decent result, but it wasn’t perfect. ZMP control requires enormous energy. ZMP control requires enormous energy.

IV. Ethics and humanoid robotics

“As an innovator and by innovator I mean anyone who has a progressive, innovative spirit and wants to move forward, we can ask ourselves the question: Who benefits from the crime? When we think that tomorrow will be a better world if we have a humanoid robot. How far are we willing to go when talking about humanoid robots? “. Sacha Stojanovic asks us, taking two examples:

- The Sophia robot, designed by Hanson Robotics:

Saudi Arabia has become the first country to grant citizenship to a humanoid. This “social robot” can recognize faces, and its own silicone facies can mimic 62 human expressions.

“The creation of a robot like Sophia, leads us to ask ourselves what is our will in terms of humanity? Indeed Sophia allows single people to have company. But is this really the answer to the problem? Or is it a disguised way to generate profits without really looking at the source of the problem? Rather, we should ask ourselves, why are there so many lonely people in this world? So much so that they need to buy machines to create relationships. »

- The retirement home animator robot

“This second example is, in my opinion, the most violent. Our society has pushed the elderly into nursing homes. Today, our society wonders how it will be possible for a humanoid robot to occupy the generations that precede us. I imagine myself in 40 years perhaps, technophile at heart, will one day I not regret my almost unconditional love for robotics?

A concept for the care of the elderly has existed for thirty years, humanitude. It might be good to ask the question if the humanoid robot is compatible with this concept. “A person very close to me once said to me, ‘If one day I find myself in a retirement home with medical robots, I would ask myself: What have I done to humanity to deserve this? “.

Sacha Stojanovic insists that social interactions should be exclusively between humans. While the machine must be at the service of people in order to make their lives easier and not to create humanity. We can illustrate his thoughts with Rabelais’ quote from Pantagruel “Science without conscience is only ruin of the soul”.

Robotics must put man back at the heart of its priorities and in accordance with the words of Charlie Chaplin “Machines should do the good of humanity, instead of causing tragedy and unemployment.” he told a journalist in 1931.

It is to promote this vision that Sacha created Meanwhile, so that “meanwhile” men and women can do something much more interesting and relevant.

Sources :

- Interview Sacha Stojanovic – Meanwhile – Founding President – Humanoid robotics

- https://sachastojanovicscpo.github.io/Fonio-doc/